Our Dust

Dear Celia, Like you, I too am a Shell Girlie, though my shell collection did not survive my family’s déplacement. You and I, the seeds of uprooted trees, we collect for posterity. But absent return, absent record, how do we compose genealogy? When you set out to wrest your family history from your father—I know your pain when you plead, why won’t you share with me?—you sought beyond his archive’s peripheries. What about all of the things that make a life a life—these not-posed and not-arranged relics of lives lived?

You could compose genealogy from still life: by asking your father to shell pistachios with you, the way he shelled pistachios for child-you, his touch tender and careful, their shells pile, arrange, rearrange: worthy of picturing, preserving. As he sprinkles and strews and pours, rosewater, cumin seeds, sumac, garlic peels, I recall you telling me of his reluctance, then his persistence to remain outside the frame. His eventual participation in your work makes my body prickle and pang with envy when I remember my own father’s reluctance; when I ask of his father’s role in a political party outlawed by Nasser, he dismisses me with a chuckle; instead he shares news of marriages, births, breakups. Perhaps petty gossip is genealogy, too. Your father couldn’t understand why you wanted to know—until he did. You console me with this record you now possess.

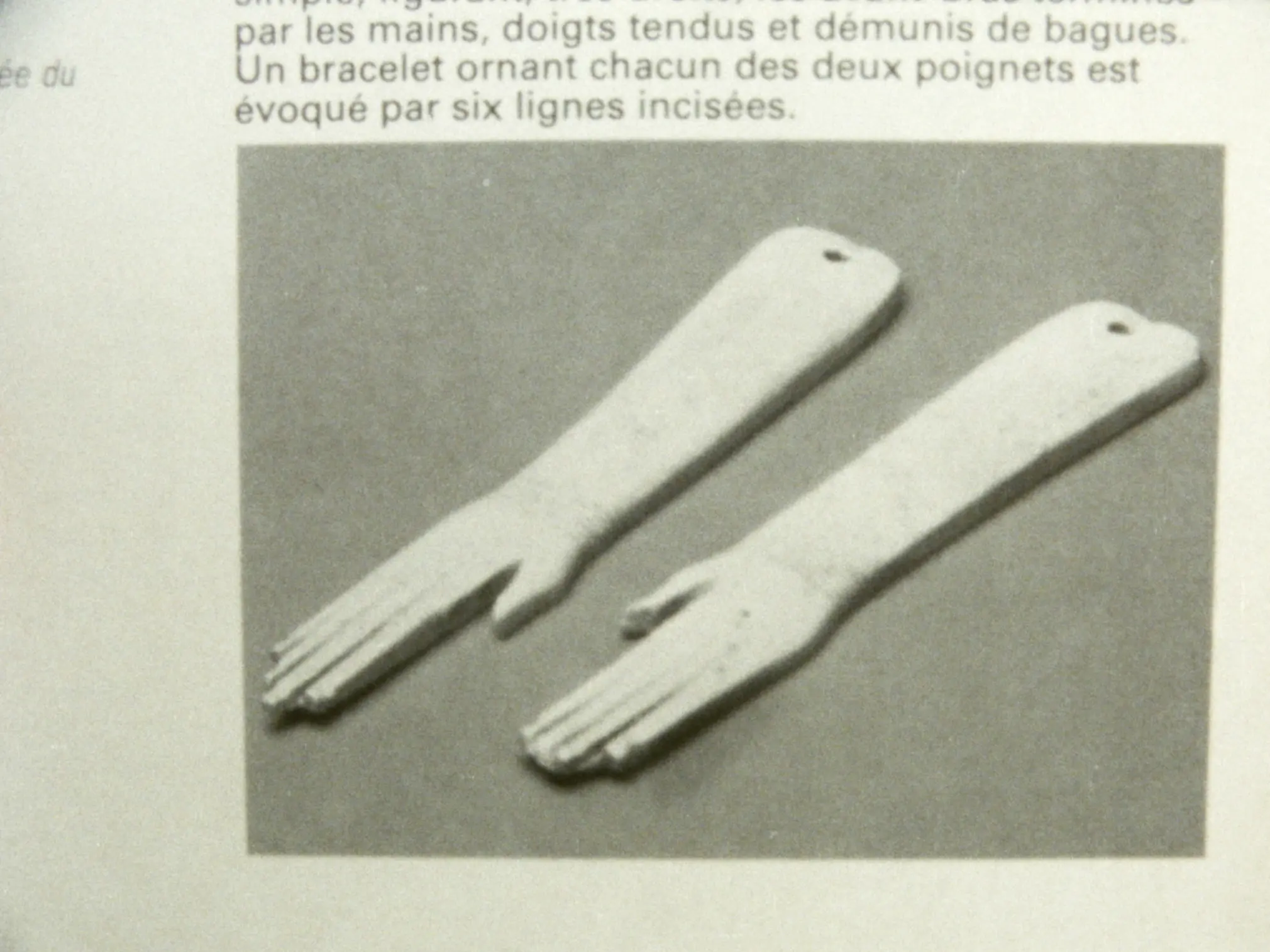

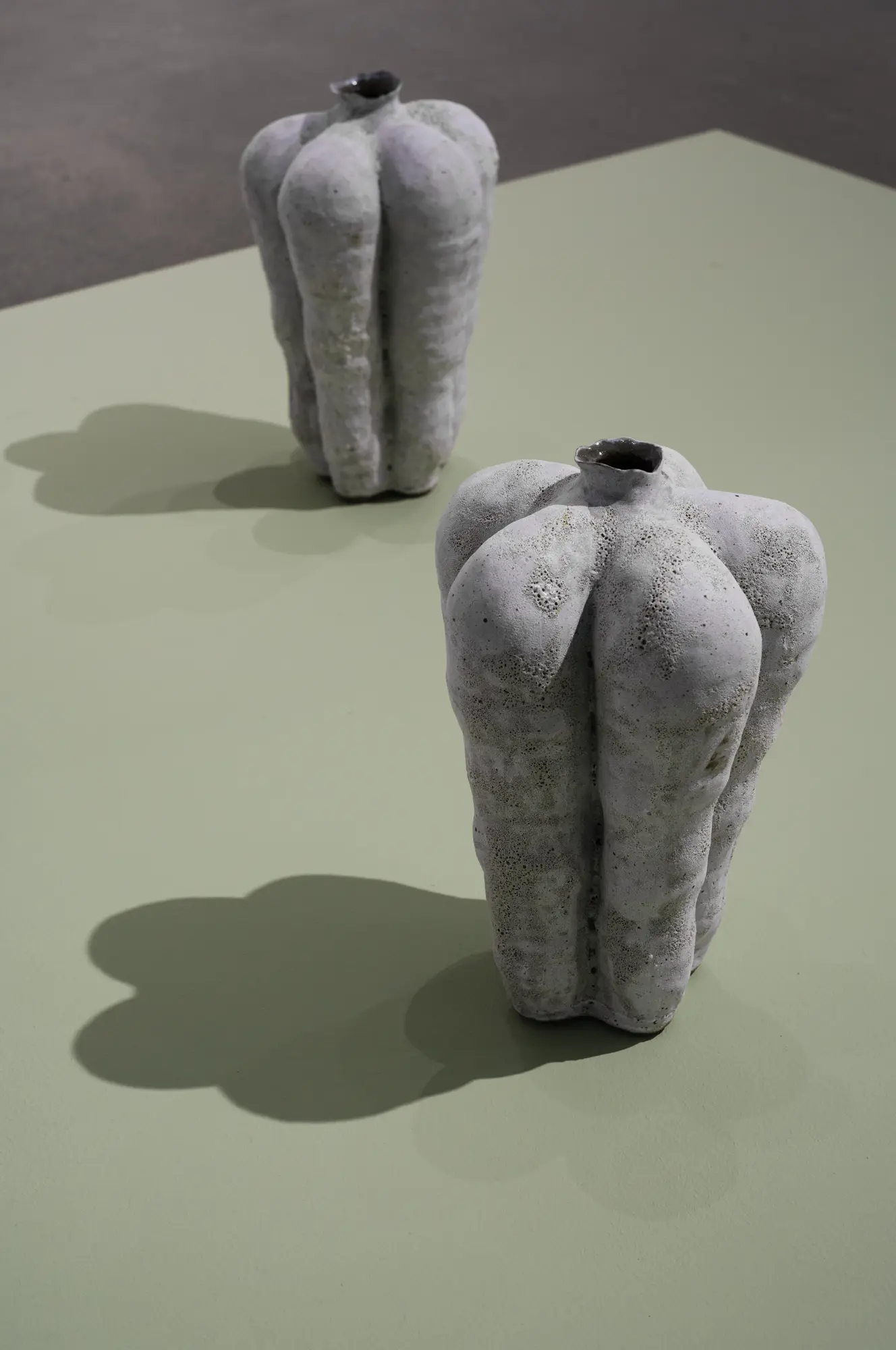

The gesture of taking apart to return together again is customary in your work, but one you had not taken to your family archive. How can re-assemblage make your ephemeral archeological? You could compose genealogy by ennobling the still life: it’s what you call an ethics for living, or an ethics for existing. You could exalt ritual, the objects that form the very basis of life. You could create containers to confine voids— vessels whose surfaces and orifices mirror each other (when one of them overflows, its flow fountain-like, propelled from within, as if with a pulsing core, against gravity, palpitates, then gushes, you remind me that a still life is never still), vessels whose clay still breathes. The vessel becomes visceral, earth skin and skin earth, clay caressed continuous with flesh. The vessel becomes body, brushes with a shell and its kernel and its empty shell cast in bronze, brushes with kneeling gods chiseled from millennia of geological time compressed into slick slabs of alabaster, granite, limestone, which brush with peels, seeds, pods, a shadow, a gaze, a guava’s avocado-like flesh, leather, satin, coral, fossil, glass, glaze, a knife’s blade, a Cairene cypress captured on a honeymoon, held hands, hair sprayed, portraits of the departed, gelatin and silver and cellulose, inscriptions of lives lived and bodies formerly inhabited and spirits ascended, their protective prayers for the living. Hands of the no-longer-here brush with the hands of the still-here. You collapse time into an accordion, constantly contracting and expanding, one in which the family album dances with the exhibition catalog from a 1985 Palais de la Civilisation exhibition of pharaoh Ramses II’s tomb, in a former Expo 67 building, outside of which your father learned of your mother’s second pregnancy.

Within your universe of evanescent arrangements, you make the fragments you took from the whole as whole as the whole; you make the fragments fluctuate, fluid, mutable and mercurial—within yet beyond, but of and from and for the same time. Ceremonial. Equally eternal.

Yours sincerely, and always, Merray

— Merray Michael Mina, text written on the occasion of the exhibition Our Dust, Patel Brown Toronto, February 2024